South Prairie Creek: A Puget Sound Dairy Farm is Restored to Steelhead and Salmon Habitat

SPSSEG’s Kristin Williamson and Cole Baldino walk along the recently restored section of South Prairie Creek where it flows through a former dairy farm.

By Greg Fitz

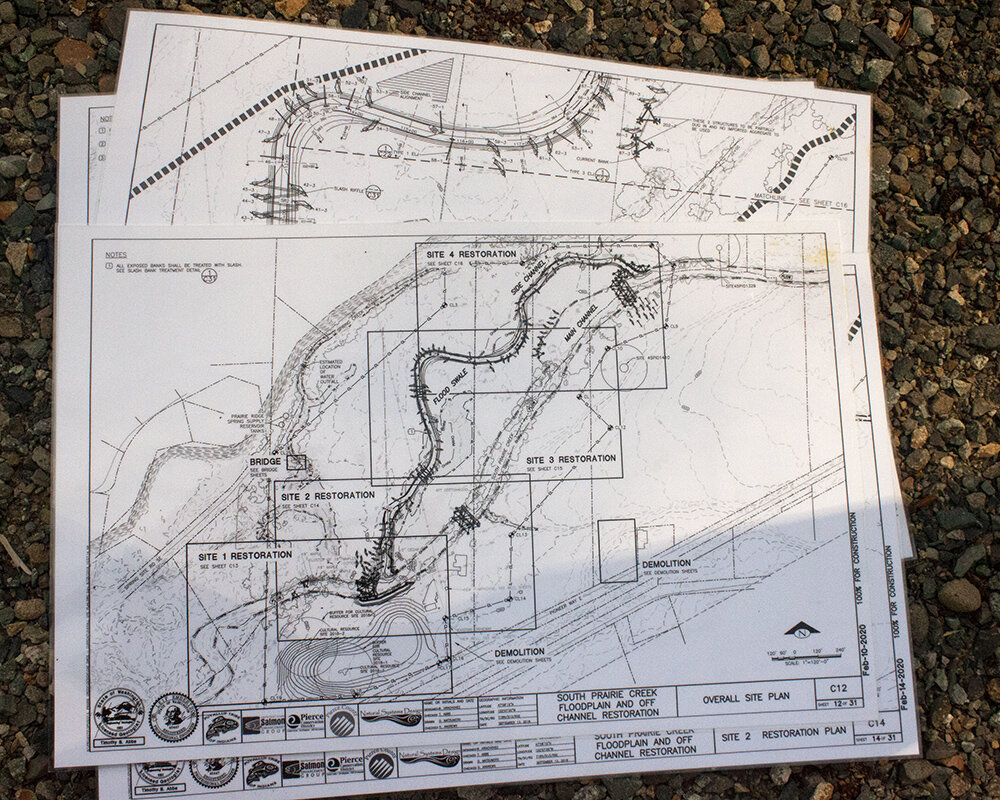

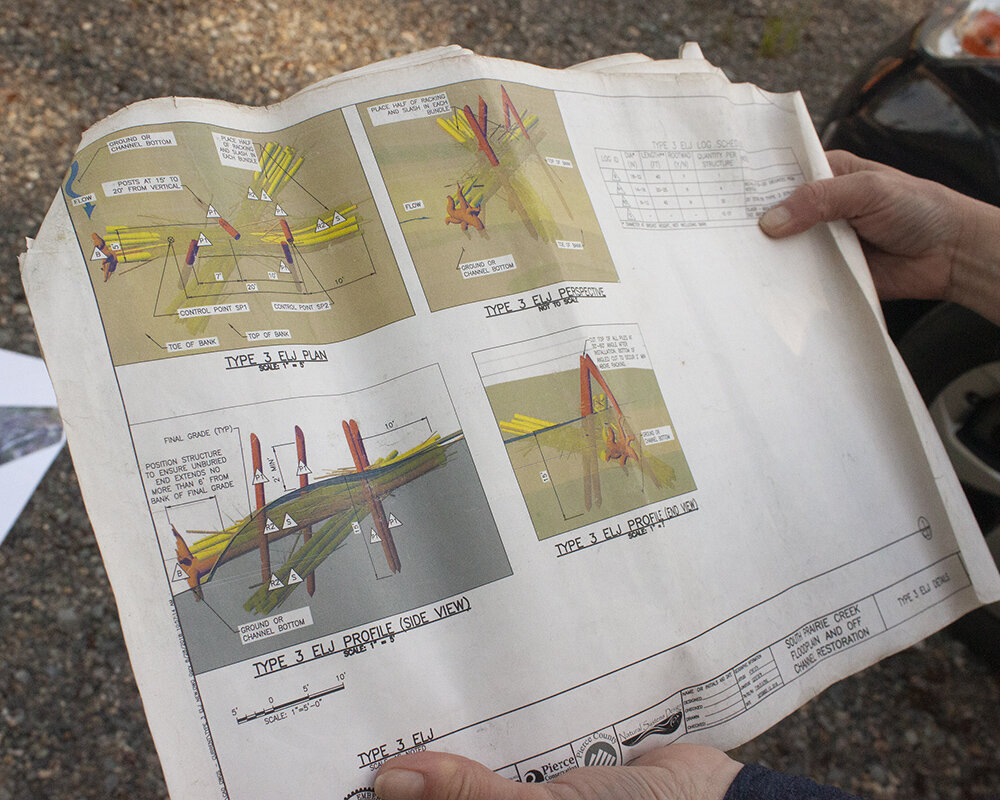

After years of planning, fundraising and engineering, last summer the bulldozers and excavators finally arrived at the site of a former dairy farm along a half mile stretch of South Prairie Creek, a tributary of Washington’s Puyallup River watershed in South Puget Sound. Over the course of eight months, the crews would remove nine buildings and their foundations, install a new bridge over a spring creek tributary, move nearly 20,000 cubic yards of earth, dig a 2600 foot long side channel, install 118 engineered log structures built using over 4600 pieces of wood, add tons of gravel and rock to the logjams, and plant thousands of native saplings and plants in the restored riparian zone along the creek.

This ambitious project to restore crucial salmon and steelhead habitat and reconnect the creek to its floodplain was the result of a long-running collaboration between the South Puget Sound Salmon Enhancement Group (SPSSEG), the Puyallup Tribe, the Pierce Conservation District, and Pierce County Surface Water Management. Washington anglers and conservationists should be thankful for their hard work, dedication, and expertise.

When the work was complete, the site had been transformed. For nearly a century, the ecological function of this cold water trout and salmon stream had been deeply compromised by the changes required to transform old-growth forest and a winding creek into open agricultural land. With watershed complexity restored, this stretch of South Prairie Creek is well on its way to returning to a forested landscape and productive habitat for steelhead and salmon.

In fact, immediately after the work was complete, juvenile salmon and rainbow trout were already occupying the new side channel and holding in the pockets of soft water behind the anchored pieces of woody debris. Adult chinook were documented spawning in the restored habitat and large numbers of aquatic insects and key macroinvertebrates were observed by scientists working at the site.

During a site visit with Kristin Williamson and Cole Baldino of SPSSEG to see the progress first hand, learn more about the project, and take photos, young salmon were visible throughout the restored stretch and small trout were rising to eat caddisflies on the surface of the creek. Seeing the fish holding and feeding in the restored stream was deeply inspiring.

While many of those small, wild rainbows will spend their entire lives in freshwater as resident fish, hopefully a few will go on to express the genetic instinct to smolt and head to sea and return years later as steelhead.

Today, like much of Puget Sound, the Puyallup Watershed bears the impacts of over a century of development that always neglected the impacts to fish populations. Much of the upper watershed was intensely logged and developed for hydropower. Lower down, land was cleared for agriculture, urban development, and flood control, all of which has had consequences for the watershed’s ability to sustain trout and salmon.

Upstream of South Prairie Creek, on the mainstem of the Puyallup, the Electron Dam was built in 1904 and blocked 26 miles of upstream salmon and steelhead habitat. It continues to degrade the river’s habitat and kill native fish as a result of its water diversion today. In July 2020, a contractor working at the dam site dumped 600 square yards of turf and at least 4-6 cubic yards of crumb rubber pollutants for miles downstream. The material had been used illegally and the pollution event has renewed calls for the dam’s removal by regional leaders, particularly the Puyallup Tribe who has filed a lawsuit over the dam operator’s violations of the Endangered Species Act.

Electron Dam is an out-of-date dam that produces very little electricity, but it has a serious impact on native fish. It is a perfect candidate for removal and hopefully we see traction in that effort soon, but the work at South Prairie Creek is important to celebrate because it highlights the need and opportunity for habitat restoration beyond barrier removal.

Dams, reservoirs, and dysfunctional culverts are obvious interventions to the function of any watershed. Removing them offers dramatic restoration gains and we should be breaching as many of them as possible, as fast as possible. But anglers should also be aware of, and seek opportunities to support, floodplain reconnection and riparian zone restoration with just as much zeal as we celebrate barrier removal. Salmon and trout need all of it.

Projects like the restored dairy farm on South Prairie Creek are an effort to help degraded watershed ecosystems return to their full ecological function by rebuilding and reconnecting habitat in ways that match how the ecosystem would have naturally evolved before it was logged. During high water events in intact Puget Sound watersheds, stream flows are slowed by fallen timber and log jams and water is allowed to flow through braided channels and spill out onto the floodplain. This keeps the ground saturated and provides time for the water to soak into the water table where it is stored until dry summer months. It lets gravel settle out of slower-moving water, replenishing spawning habitat in the process. Side channels, access to the floodplain, and logjams also give juvenile fish a place to rest during floods and winter flows instead of being swept away. They also help prevent the river bed from being scoured, which can destroy redds and aquatic insect habitat.

The wood piles are an important source of shelter from predators, especially during periods of low water. By deflecting some amount of current, logjams also create pools where juvenile and adult fish hold. As groundwater is replenished these pools become crucial thermal sanctuaries for cold water fish and aquatic insects. The bottom of the pools intersect with the water table, allowing groundwater to seep through the stream bed. In the summer, this exchange is a crucial source for cold water where fish can survive during hot, dry conditions. In the winter, it does the opposite. Because groundwater is a relatively consistent temperature year round, the pools are often warmer than the cold rain and snow melt feeding the river in the winter. This provides ideal temperatures for juvenile trout and salmon rearing and growth when the rest of the river might be flowing too fast and too cold.

The work at South Prairie Creek is only a little over a year old, but already the former dairy farm is showing early, encouraging signs of recovery. Fish and aquatic insects are using the habitat and water temperatures are already improved. The engineered logjams will serve to stabilize the streambank during high water events and give the planted saplings time to grow and reforest the former pasture in the coming decades.

Best of all, the partners responsible for this project are just getting started. This was the first major habitat project to be undertaken on this section of South Prairie Creek, but planning is underway for additional restoration efforts on property upstream and downstream of the site. This crucial tributary of the Puyallup watershed is getting the investment it, and South Puget Sound’s native salmon, steelhead, and trout, deserve. The positive impacts of this work are immediate, but the recovery will continue to build upon itself as time passes.

Chinook and steelhead holding in the restored pool are proof of the project’s viability and importance, but it is the subsequent generations of salmon and trout born, grown, and spawning here that will be the real return on investment. After a century of degradation, this portion of the Puyallup watershed is healing.

All of us who care about the future of wild steelhead and salmon in the Northwest should take a moment to celebrate this work. It should give us hope, but it should also inspire all of us to make sure these projects are repeated in as many of our rivers and streams as possible.

/ / / / / / / /

A huge thanks to Kristin Williamson and Cole Baldino of the South Puget Sound Salmon Enhancement Group for the tour of the project on South Prairie Creek.

Learn more about SPSSEG’s work to reconnect and restore wild salmon and steelhead habitat across South Puget Sound watersheds at this beautiful story map created to celebrate their 30th Anniversary.

Please Note: South Prairie Creek is currently closed to fishing while recovery work is being done.